peter k jenkins

“Grand Paris: Envisioning the First Post-Kyoto Metropolis” 2011

The Synopsis of which was published in ASSOCIATION Vol. 11 in 2020.

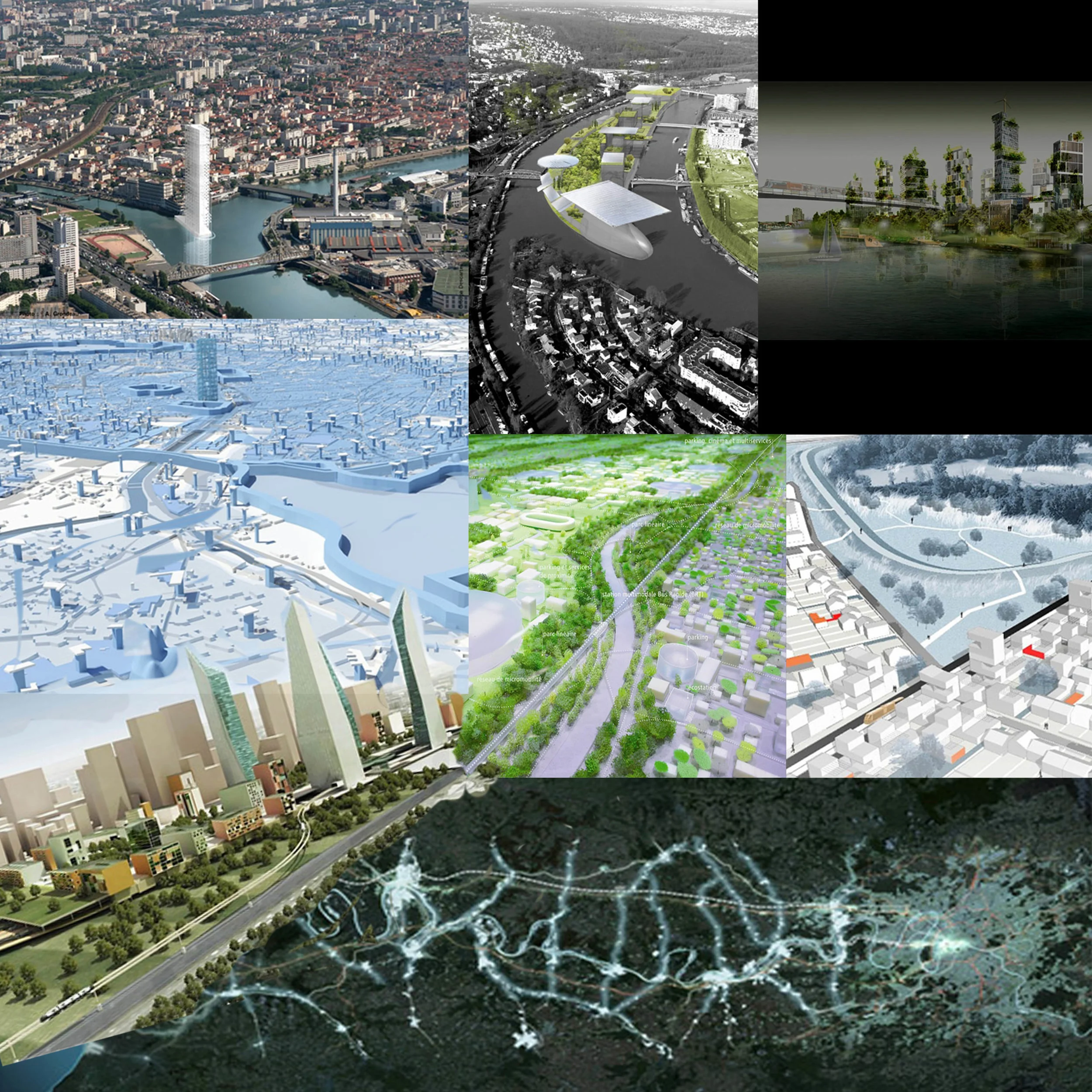

Graphic Design by Peter Kelly Jenkins 2019. Images from the Grand Paris teams 2009.

ASSOCIATION Volume 11

Synopsis page 10

Page 19. Synopsis Quote.

Grand Paris: Envisioning the First Post-Kyoto Metropolis

By Peter Kelly Jenkins: pkj5, Department of City & Regional Planning ‘06,‘10

Defended Fall 2010, New Synopsis written December 2018, Published 2020

Faculty Advisors: Stephan Schmidt and William Goldsmith

We here attempt to illustrate how two plans from the Grand Paris urban design competition address the challenges of the post-industrial and post-Kyoto metropolis. As is evident from the failure of modernist planning, present urban design does not contain a singular functionalist or Utopian form universal to any site, as recommended in Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter and represented by his Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) plan. Instead, Andrea Branzi’s New Athens Charter recognizes that 21st-century urbanism is not uniform and must be continually managed, redesigned, and reshaped in reference to the site.

Grand Paris is a series of speculative urban design solutions by ten teams in an effort to increase the ecological and social health of metropolitan Paris in an era of climate change and deepening spatial inequality. Two of its fundamental goals are to significantly reduce carbon emissions and to address the physical and social disconnect between Paris proper and its surrounding banlieues (underserved suburbs). Here exist the challenges of Post-Kyoto green design. The ten Grand Paris teams approach the latter goal through regional transportation planning, using urban designs that connect and honor the social inclusion of residents of les banlieues over the potential real estate interests of an elite class of financiers and developers.

The teams employ a variety of designs, planning approaches, and inter-scalar infrastructural innovations that envision a sustainable future for the Parisian region. The teams were tasked with diagnosing the ailments of contemporary Paris by taking a regional perspective to prescribe methods to improve the health of Europe’s largest urban agglomeration. Common solutions involve enmeshing the built and natural environments, developing new transport networks, and focusing on ecological design, all of which acting to repair scars from a 20th-century modernist design by threading suburban administrative areas to central Paris and to other suburbs. This typology of design is most prevalent in les banlieues outside of le peripherique (ring road) surrounding Paris proper and its 2.1 million residents. Many teams re-purpose elements of 20th century modernist design, including renovating social housing; re-activating under-utilized industrial infrastructure; and designing elements of the public realm that prioritizes pedestrians, cyclists, as well as a pluralistic social theatre operating within the agora of an evolving Parisian polity.

‘Les banlieues’ often have a derogatory connotation in traditional French culture, referring to blighted suburban administrative areas outside of le peripherique, that are primarily home to emigrated communities from Francophone African countries, particularly those of North African and Muslim descent. The objective definition of a “banlieue’ refers to suburban administrative areas outside of a ‘city proper’ in France. Residents of ‘la banlieue Parisienne’ have reduced access to education, jobs, and quality transportation. These communities are policed in a more authoritarian and exploitative manner. This oppressive policing approach sparked the French Riots of 2005, which ignited in le banlieue de Clichy-sous-Bois. The riots internationally broadcasted the dire tensions between a young male underclass and policing methods that, at times, include unwarranted fatal force. Community blight, isolation, and failed social housing are three ailments of les banlieues. The built and natural environments are far less livable than those of central Paris. Consequently, an important component of the Grand Paris competition explores methods to reconnect the heart of Paris to its often-neglected limbs, to promote greater mobility and regional economic integration.

We selected two plans out of the ten formulated by the Grand Paris teams in which to analyze four components critical to achieving increased sustainability and carbon reduction: greenspace, housing, transportation, and waterways. The two plans adopted dramatically different approaches. Team Rogers focuses on a green retrofit of the existing Parisian urban area, while Team Grumbach proposes population diffusion from central Paris to new towns built along the Seine River.

Part of Team Rogers’ plan involves a series of ambitious green armatures, or greenways, built over underused rail lines that connect to an urban growth boundary; Team Grumbach proposes a linear extension west of Paris along the Seine River to Le Havre, to create a Seine Metropolis. Both plans are analyzed using the framework of Philip Berke and Maria Manta Conroy’s article “Are We Planning for Sustainable Development?” This framework is used to evaluate the extent to which each plan achieves the goals of equitable and holistic green planning. The two plans are also vetted through Ken Yeang’s research on environmental design, which seeks to harmonize four sets of urban infrastructures to increase ecological self-sufficiency. While differing greatly in their design approach, both Group Rogers and Group Grumbach aim to accomplish a similar goal: the creation of a resilient and connected region far exceeding the climate change targets outlined in the Kyoto Protocol.

In Grand Paris, teams have taken a necessary step in coming to terms with Paris’ current size and demographics beyond le peripherique. A state rescaling is much needed, considering that 80% of people in the Parisian metropolis live outside of the city proper. This political rescaling, emanating from Paris proper and flowing to the periphery, may impact the sociocultural and economic crises of les banlieues, primarily through gentrification and displacement. More broadly, the Grand Paris teams are envisioning Paris as becoming the first Post-Kyoto metropolis by significantly reducing carbon emissions in the city and its surrounding suburbs. In this, the Grand Paris competition is the first time a global megacity has initiated an international conversation on how to plan, design, and retrofit for significant carbon reduction, equity, and increased regional connectivity in the 21st century

Grand Paris, as it enlarges the focus to the Parisian region, may influence real estate trends and potentially provide fuel for speculation in new territories, wrapped in a design package that celebrates green urban futures. However, the Grand Paris urban design competition, if solely a project in ecological urbanism, provides politicians with creative and bold plans to lower carbon emissions, as outlined in the Kyoto Protocol, and increase environmental resilience; against, for example, the 2003 Paris heatwave that killed 3,000. The importance of decreasing the ecological footprint of this advanced global city is aptly approached in the Grand Paris competition. Accordingly, the public sector must work across bureaucratic silos to plan at this grand scale, while working with designers to envision a beautiful, just, and sustainable future for one of the world's most esteemed metropolises.